Iron Overload: Ferritin, Toxic Overload, Liver Inflammation and Brain Health

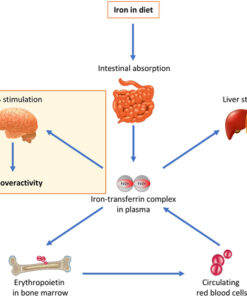

Iron, a critical mineral, is necessary for our bodies' normal functioning. However, it can become detrimental when its levels surpass the body's capacity, leading to iron overload and consequential health complications such as oxidative stress, liver damage, and more.

Iron Overload and Oxidative Stress. The dual nature of iron - essential for the body's functioning yet potentially harmful when there's an excess.

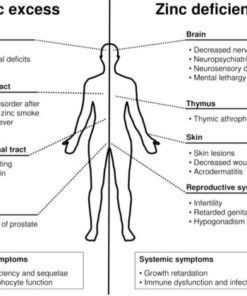

Iron Toxicity: Iron homeostasis is crucial because both deficiency and excess can lead to adverse effects. Iron toxicity occurs when the iron-binding protein capacity is exceeded. The toxicity arises from iron's ability to generate free radicals and act as a growth factor for pathogenic microorganisms and neoplastic cells. Excess dietary iron can interfere with the absorption of other divalent metals.

Iron and Oxidative Stress: Excessive iron accumulation increases non-transferrin-bound iron leading to free radical generation. The small intestine, the primary site for iron absorption, is most affected by this, leading to increased oxidative stress. This can cause cellular changes and increased intestinal barrier permeability, leading to cell death and potentially allowing substances like bacterial toxins into the bloodstream.

Iron and Microbiota: Iron supplementation can have adverse effects on the intestinal microbiota. The excess unabsorbed iron involved in Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions can negatively impact the intestinal structure and the composition of the gut flora. Certain pathogenic bacteria can capture iron from ferritin and transferrin using siderophores. Commensal bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium don't require much iron to grow.

The gut microbiota can control systemic iron homeostasis by inhibiting intestinal iron absorption pathways and by increasing cellular iron storage. Lactobacillus plantarum has been shown to increase iron absorption in iron-deficient females. Oral iron supplementation has shown mixed results on gut microbiota, sometimes reducing beneficial microbes and increasing harmful ones, other times promoting commensal bacteria and increasing intestinal microbiota metabolic activity.

These findings suggest the complex interplay between iron and microbiota, where both negative and positive impacts are reported, underscoring the need for further research, especially concerning the potential harm of untargeted iron supplementation.

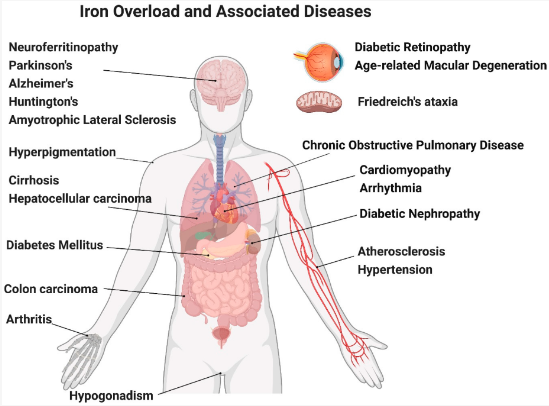

Excessive Levels of Iron in Age-Related Diseases

Iron levels in the body typically increase with age due to dietary iron intake, genetic factors, and repeated blood transfusions. Accumulated iron can contribute to the formation of free radicals, contributing to various diseases, such as arthritis, cirrhosis, cardiomyopathy, and many more.

Iron accumulation is implicated in various neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, Huntington's, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Iron can exacerbate the misfolding and aggregation of certain proteins, hallmarks of many of these diseases.

Iron deposition in the heart can cause arrhythmias, systolic dysfunction, cardiac hypertrophy, and cardiomyopathy. Iron chelation has potential therapeutic roles in managing these conditions. Moderately elevated iron and ferritin levels are associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, independent of other known risk factors. Iron overload may also accelerate damage to organs during diabetes.

Iron is suggested as a risk factor for many types of cancer, including liver, colorectal, breast, and lung cancer, due to its prooxidant activity. Hemochromatosis patients with iron overload often present with cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma.

Iron present in cigarette smoke is known to cause pulmonary damage, contributing to the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In addition, iron accumulation has been implicated in rheumatic conditions like arthropathy and osteoporosis, often seen in patients with hemochromatosis, a disorder of iron overload.

Elevated iron levels can also support microbial growth, hindering the body's inflammatory responses and leading to an increased risk of infections. Iron overload can lead to dysfunctional bacterial phagocytosis, affecting the host’s immunity.

Foods Fortified with Iron:

The most significant source of iron is dietary supplements and fortified foods, quite often it comes in the form of elemental iron. Although these can benefit those with iron deficiencies, they can also contribute to excess iron intake for others. As such, it is critical to identify foods that contain fortified iron and ensure a balanced diet that aligns with individual nutritional needs.

Iron-fortified foods are have traditionally been thought of as an important source of dietary iron, especially for individuals at risk for iron deficiency, such as infants, young children, pregnant women, and people with certain health conditions. However, there is serious controversy surrounding the use of elemental iron in these foods.

Types of Iron Used in Fortification

There are two main types of iron used for fortification: elemental and non-elemental. Elemental iron powders are often used due to their lower cost and longer shelf-life, but they can cause issues with the taste and color of food. Additionally, the body doesn't absorb elemental iron as well as non-elemental iron. Non-elemental iron includes compounds like ferrous sulfate and ferrous fumarate, which are more easily absorbed but can be more expensive and may still alter the taste or color of foods.

Controversy Surrounding Iron Fortification

One key controversy revolves around the potential for iron overload, especially in populations with a high prevalence of genetic hemochromatosis, a condition that leads to excessive iron absorption. Excess iron intake from fortified foods can also contribute to conditions like oxidative stress, inflammation, and other health issues.

Moreover, there are concerns about the bioavailability of the iron used in fortified foods, particularly with elemental iron powders. The body's ability to absorb this type of iron is limited, making it less effective at preventing or treating iron deficiency.

Additionally, there's the issue of the 'nutrition transition', where developing countries are shifting towards more processed, Western-style diets. This often leads to an increase in the consumption of iron-fortified foods, potentially contributing to iron overload in certain population groups.

Prevalence of Iron Fortification In terms of prevalence, many staple foods and commonly consumed products are fortified with iron, especially in developed countries. These include:

- Breakfast cereals: Many cereals are fortified with 100% of the daily value for iron per serving, making them one of the most common sources of dietary iron.

- Flour: Many countries mandate the fortification of wheat flour with iron to combat iron deficiency.

- Rice: Iron-fortified rice is becoming more common, especially in countries where rice is a staple food.

- Pasta: Similar to flour, many types of pasta are also fortified with iron.

- Baby formula: Almost all infant formulas are fortified with iron to meet the high iron needs of growing infants.

- Fortified nutritional drinks and meal replacements: These products often contain added iron.

Testing Ferritin Levels to Rule Out Iron Overload as Cause of Inflammation

Testing Instances of iron deficiency can occur due to factors such as chronic disease, heavy menstrual periods, intestinal bleeding, and blood disorders. It is likewise common to encounter cases of iron overload due to excess iron intake or conditions like hemochromatosis and elevated ferritin levels, associated with leaky gut. Ferritin testing plays a pivotal role in these scenarios, as ferritin is a key biomarker for the body's iron storage. Elevated serum ferritin levels may signal an iron overload situation, warranting immediate medical attention.

At Second Opinion Physician, we strongly advocate for regular ferritin testing. Ferritin serves as an essential biomarker for the body's iron storage, and elevated serum ferritin levels may signal an iron overload situation. When dealing with iron deficiency anemia, our approach focuses on pinpointing the cause of abnormal bleeding or on enhancing digestive health. The latter aims to improve the absorption of a varied and nutrient-rich diet, providing the body with a balanced mix of essential nutrients. When levels of ferritin are above 30ng/ml, functional medicine physicians are inclined to recommend supplements to remove copper from the intestines before it is absorbed in the blood.

Inositol hexa phosphoric acid (Phytic Acid) Supplement Benefits in Iron Binding:

A Potential Natural Solution? A study published in Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy highlights the potential of phytic acid as a natural solution to iron overload. Phytic acid, a potent antioxidant, shows promise in reducing iron-induced oxidative stress and even alleviating liver injury in mice suffering from iron overload.

Phytic acid was shown to significantly reduce biochemical markers such as serum iron, total iron binding, serum ferritin, and serum enzymes through oral administration. It also displayed the potential to down-regulate inflammatory mRNA expression (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6), potentially reducing inflammation in iron-overloaded liver tissues.

Phytic acid's potential extends to serving as a dietary hepatoprotective supplement and an iron chelator for diseases related to iron overload.

Iron Accumulation in Neurodegenerative Disorders Research shows significant links between iron metabolism and Parkinson's Disease (PD). Excessive iron accumulation in the brains of PD patients, causing oxidative stress, leads to the degradation of nigral dopaminergic neurons, a characteristic feature of the disease.

Iron's role in neurodegenerative disorders might extend beyond Parkinson's disease, impacting diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS), dementia, chronic headaches, and conditions like leaky gut syndrome. This points to the need for regular testing and careful management of iron levels in patients diagnosed with or at risk for such disorders.

Phytic acid is suggested as a potential treatment or preventative measure given its demonstrated ability to chelate iron, thus preventing its accumulation and subsequent harmful effects.

Other Therapeutic Approaches Reducing Iron

In severe iron overload, other methods for reducing iron levels may be employed to prevent the incidence and progression of chronic diseases. Common treatments include repeated phlebotomy and the use of iron chelators. Desferrioxamine is a commonly used siderophore for chelation therapy.

Natural chelators, derived from various plants and spices, that can help manage iron levels include curcumin, floranol, phytic acid, genistein, quercetin, and others. While these natural substances have potential, more research is needed to determine safe and effective dosages.

Article references:

- "Neuroprotective effect of the natural iron chelator, phytic acid in a cell culture model of Parkinson's Disease" - Qi Xu, Anumantha G. Kanthasamy, and Manju B. Reddy

- "Role of Iron in Aging Related Diseases" - William J. Chen et al.

- "The Dark Side of Iron: The Relationship between Iron, Inflammation and Gut Microbiota in Selected Diseases Associated with Iron Deficiency Anaemia—A Narrative Review

Iron and Gluten, The Toxic Tandem – Thomas E. Levy, MD, JD

Cardiologist, Thomas Levy, M.D. walks us through the effects of iron and gluten on the body and the positive and negative effects of a iron and gluten regulated diet.

Testing Metal Overload,;Iron (Ferritin) and Copper

Other Single Item Tests

All Cognoscopy Labs

All Cognoscopy Labs

All Cognoscopy Labs

Walsh Approach Test Panels